We have now returned to Toronto!

So! A number of the team have experience of being away from home - I've been going to the field for many years, as has Joelle, and Francesca had her year-long stint in South Africa. One thing we all agreed about was communications from the field to our loved ones: short, to the point, and always positive. Since e-mail communication has been very difficult, this has been easy to maintain, except perhaps for when we hit the internet cafe in Aleppo! But they always remained positive. It seems that the team philosophy, as is that of any experienced field person to my knowledge, is that the objective is not to make your loved ones worry. If you are sick, or having deep thoughts about a relationship (including those with parents!), you keep it to yourself. The philosophy is just to come home to them, and sort it out from there. If they get upset that they were never told about the race to the hospital, you just shrug, and ask them why they thought it would help the situation if you were knowing they were immersed in futile worrying while you were struggling with, say, a chest infection. We also didn't tell people about our travels much, or, more specifically, how close those travels brought us to the Lebanese border. It had been my intention not to take the team to places like Saidnaya (within sight of Ba'albek), or Qal'at al-Husn (Crac de Chevalier - this would mean traveling along the strategic Homs pass about 10 km from northern Lebanon). However, after we arrived in Syria, and the team felt so incredibly comfortable with the welcome afforded by the Syrian people, and the security they felt not just in the monastery but anywhere in Syria, it was agreed that we would go to these places. But our loved ones did not feel that security like we did, so they would have only worried if they knew.

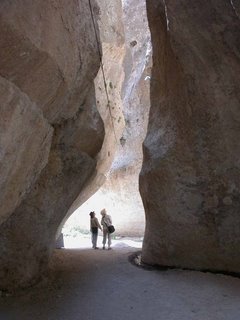

My problem was my foot. The occasional picture you may have seen of me with a walking staff was not because I thought that my leadership image might be helped by it (whether trying to seem more like Moses or Gandalf being a mute point). The fact is that I had broken my foot (nasty break of the 4th metatarsal) and had seriously twisted my ankle a couple of months before leaving, and the cast had only come off two weeks before leaving for Syria, after being in it for over 6 weeks. Needless to say the bone physician at the hospital thought the idea of mountain climbing in Syria with a broken foot to be fundamentally absurd, which is really not the sort of thing to say to me if you don't want me to do something. "Absurd" is the sort of term that gains my positive attention as quickly as terms like "chocolate" or "Australian Shiraz". The foot actually created quite a few problems. It was particularly cranky in the morning, which made the 5:30 am starts I had planned an impossibility (much to everyone's deep regret, I'm sure); and made all the climbing a lot more worrying and dangerous. The tale of the walk by moonlight may have been given a little extra zest if I had recounted how many times my walking staff, or my massive hiking boots, had saved my life that night, but I really didn't want anyone to worry! Towards the end, though, I started taking more risks - hence the "Over the Top" posting!!

But in the end we all survived, got a lot done, and then returned in one piece to the loved ones that we had said we would return to.

Robert

So! A number of the team have experience of being away from home - I've been going to the field for many years, as has Joelle, and Francesca had her year-long stint in South Africa. One thing we all agreed about was communications from the field to our loved ones: short, to the point, and always positive. Since e-mail communication has been very difficult, this has been easy to maintain, except perhaps for when we hit the internet cafe in Aleppo! But they always remained positive. It seems that the team philosophy, as is that of any experienced field person to my knowledge, is that the objective is not to make your loved ones worry. If you are sick, or having deep thoughts about a relationship (including those with parents!), you keep it to yourself. The philosophy is just to come home to them, and sort it out from there. If they get upset that they were never told about the race to the hospital, you just shrug, and ask them why they thought it would help the situation if you were knowing they were immersed in futile worrying while you were struggling with, say, a chest infection. We also didn't tell people about our travels much, or, more specifically, how close those travels brought us to the Lebanese border. It had been my intention not to take the team to places like Saidnaya (within sight of Ba'albek), or Qal'at al-Husn (Crac de Chevalier - this would mean traveling along the strategic Homs pass about 10 km from northern Lebanon). However, after we arrived in Syria, and the team felt so incredibly comfortable with the welcome afforded by the Syrian people, and the security they felt not just in the monastery but anywhere in Syria, it was agreed that we would go to these places. But our loved ones did not feel that security like we did, so they would have only worried if they knew.

My problem was my foot. The occasional picture you may have seen of me with a walking staff was not because I thought that my leadership image might be helped by it (whether trying to seem more like Moses or Gandalf being a mute point). The fact is that I had broken my foot (nasty break of the 4th metatarsal) and had seriously twisted my ankle a couple of months before leaving, and the cast had only come off two weeks before leaving for Syria, after being in it for over 6 weeks. Needless to say the bone physician at the hospital thought the idea of mountain climbing in Syria with a broken foot to be fundamentally absurd, which is really not the sort of thing to say to me if you don't want me to do something. "Absurd" is the sort of term that gains my positive attention as quickly as terms like "chocolate" or "Australian Shiraz". The foot actually created quite a few problems. It was particularly cranky in the morning, which made the 5:30 am starts I had planned an impossibility (much to everyone's deep regret, I'm sure); and made all the climbing a lot more worrying and dangerous. The tale of the walk by moonlight may have been given a little extra zest if I had recounted how many times my walking staff, or my massive hiking boots, had saved my life that night, but I really didn't want anyone to worry! Towards the end, though, I started taking more risks - hence the "Over the Top" posting!!

But in the end we all survived, got a lot done, and then returned in one piece to the loved ones that we had said we would return to.

Robert